|

Intro

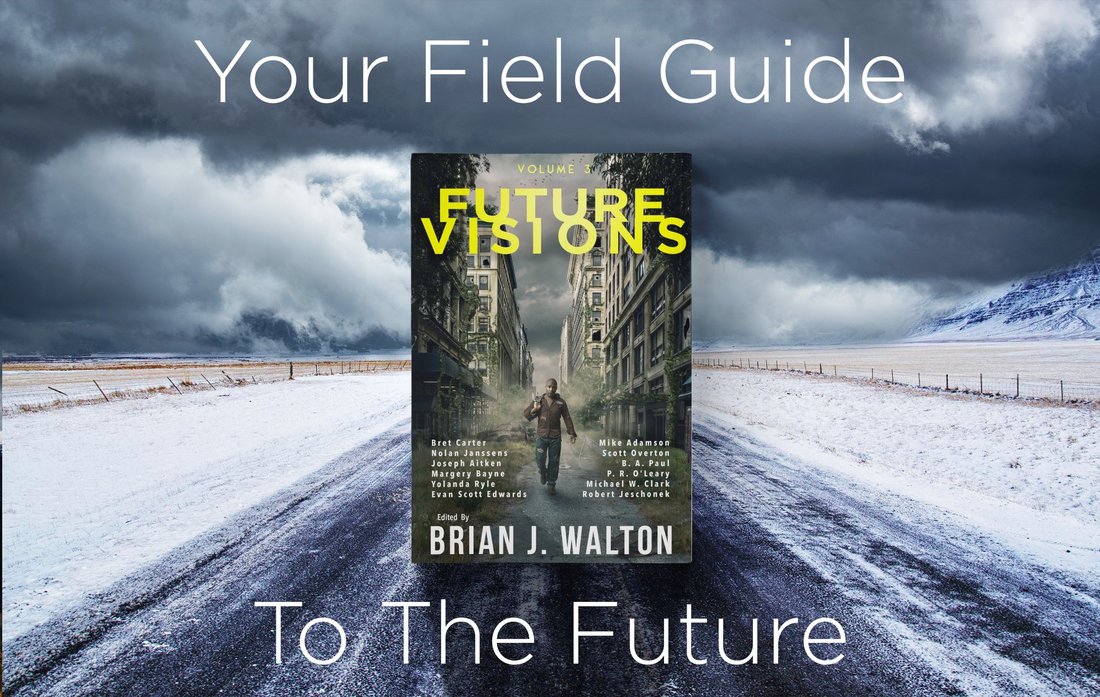

With great aplum I would like to announce that my story “Another Life” has found a home in Vol 3 of the sci fi anthology series Future Visions. Buy it here. “Nothing’s been right since Dana awoke from 23-year long coma: she hasn’t aged a day, her memories don’t feel like her own, and her husband Ben is having locked door meetings with her doctor. Secrets are being kept from her, and she’s going to figure out what they are.” I don’t want to spoil this story, a la the secrets Dana is seeking out, so below in “Behind the Story” I will only talk in broad strokes about “Another Life” Themes What makes us human? This is a question proposed in a lot of science fiction as technology encroaches on our lives, for good and ill, and as technology advances in intelligence and human capability. Is our memories downloaded into a computer our continued existence or just a computer with memories? Can artificial intelligence reach the point of humanity? What standard even is that? What about androids? What about clones -- separate individuals or the same? How much of us can become technology and still be us? Are we bodies or brain or souls? I took that classic quandary of what makes us human and what defines are personhood, and grafted that together questions of womanhood. At the time of writing, I was having a lot of personal anxiety about my personal identity and role in the world as a woman in terms of the set roles that are often expected of us. Motherhood, marriage, taking your husband’s last name, etcetera and so on. This definitely comes across in this and some other short stories I wrote about the same period. I think those themes of sci fi personhood and female identity converge as natural metaphorical partners. It sounds so deliberate and grand when I explain it like that, but it was a lot more intuitive in the actual writing. I’ve realized certain anxieties and opinions that have influenced by writing after the fact. Writing Process I recall having a very specific vision for “Another Life” with the ending known and very specific beats imagined along the way. So I wrote it, beginning to end, hitting those beats and coming to the end in a pretty painless experience. Reviewing it, however, I quickly saw that all that emotional beats I had imagined weren’t enough to support the entire story. The ‘twist’ reveal of the end came out of nowhere and needed better set up. My rewrites of “Another Life” were, in this case, mostly additive. This experience speaks a lot to my process of writing. What draws me to the story is the characters, the themes, or the emotional beats. Plot is of secondary interest. Plot is something I have to work on and build more deliberately. Favorite Line “It was just there. Like paint on the wall.” Sorry, this post is long enough, but I can’t help to stop and highlight one of my favorite, perhaps innocuous lines. I remember writing this line. I remember where I was when I wrote it. That’s how much I like it. If you haven’t read “Another Life” yet this line drops when the main character Dana comes to a certain realization. She is lying awake in bed, on her side, back to her husband. I like this line because it implies a lot, it is a metaphor so integrated in the scene it is barely a metaphor. Like the wall she is staring at and finally noticing the paint color that has been there surrounding her the entire time, so to does she this revelation come to her. Just there. Like paint on the wall. Conclusion This and “The Pawnshop of Intangible Things” are two of my favorite short stories I’ve written. I have been shopping around “Another Life” for a while and have never wanted to give it up to a throwaway magazine. I’m excited that it found its place in this rather cool indie published venture of Future Visions and editor Brian J. Walton. I’ll probably write a blog on that experience when I’m a little farther down the road with it than now. There is limited time discounted pricing on the ebook for launch week only, so check it out now.

1 Comment

A few months ago, I was sitting in the audience of a literary panel for “Writing Characters with Agency” at Balticon, a science fiction and fantasy convention in Baltimore. During the panel, one of the audience members asked for writing advice on how to keep characters internally consistent when making them do something essentially “out of character” using an example of a lawful good character doing a bad thing. While the panelist shared many a insight, this question got my brain turning and coming up with answers that were not brought up at the time.

So I’m sharing them here. So how you keep a character “in-character” and consistent while also working to a moment where they break that mold? For the sake of this, I will use the audience member’s example of a character who is lawful good do something bad. (“Lawful good” is a Dungeons and Dragons moral alignment that writers, readers, and nerds all over the internet will align their favorite characters too. Learn more here.) So let’s break down some different ways to get characters do believably do “out of character” things. The Break Down 1 - Character Development Character development can be either positive (with the characters become more brave, heroic, or “morally good”) or negative (with the characters becoming crueler, more selfish, or more evil). I bring this up, because many people only think of a character development in the positive direction -- becoming a better person -- but it can work in the other direction. Walter White from Breaking Bad is a great example of negative character development, in that he becomes a more morally bankrupt person as the show progresses, starting out with understandable and sympathetic motives for his life of crime, but slowly becoming more power-hungry and/or more willing to do more and more drastic things (like murder) to keep on top. A character can start out good and then through a series of circumstances, conflict, and drama that we will call the plot, slowly turn into a worse person. 2 - Conflicting Motives/Trolley Problem Another point to remember is that people are complicated, conflicted, and complex. We have multiple belief systems, motivations, wants, and needs in our head at the same time. Say we have our lawful good character. He is sheriff, a law man, who believes all crime should be stopped and put to justice because them are the rules. But he is not just a sheriff. He’s a family man whose family is the most important thing in the world to him. He loves them and would do anything for them to protect them and keep them happy. And now it turns out his adult son is the no good head of the gang of bandits that have been terrorizing the local towns. And it is a trusty sheriff that has been called on to stop him, dead or alive. Opps, now our character has to choose between upholding his moral system about the law or his moral system about his family. I like option above because it is very internal, but you can also give your characters bad and worse options in an external conflict. Give them a trolley problem. Think of all those superhero films where the villain gives the hero an option to save like their girlfriend/sidekick or some innocent kids/the entire city. Usually the superheroes come up with the third option to save everyone, but not always (Ahem, the Dark Knight.) But much better is when the character has a much more active hand in the dark, bad and worse option. The ending of season 3 of the BBC show Torchwood had one of these. Make your character’s options a trolley problem. 3 - Breaking Points Human beings… we’re complicated. We have belief systems but we are often hypocrites. We give ourselves or loved ones a pass when we wouldn’t give the same benefit to strangers or acquaintances. Beyond hypocrisy and exceptions, we have breaking points. On tv tropes, that can sometimes be called a berserk button. Find a character’s breaking point and them drive to it. But this all these examples lead up to this ultimate fact of writing characters and stories: It Needs To Be Earned We say that a lot in storytelling and fiction writing. That… twists need to be earned. That sad deaths need to be earned. That endings need to be earned. Relevant to here -- when a character is driven to that breaking point, you as the writer need earn that. And all the other examples listed above. But what does that mean? In screenwriting, because I watch a lot of film criticism youtube videos, the idea is phrased as: set up, reminder, and pay off. In writing, we talk about foreshadowing. I had a professor in college who always called these things “rehearsals” which is a really apt metaphor that I think should exist more preventable in the creative writing discourse. When I took dance classes as a youth at the end of the season we had a dance recital, but not until we had the stage rehearsal and dress rehearsal beforehand. If you are going to have a lawful good character do something morally reprehensible, you need to hint -- and in an escalating manner -- that he can do something bad. To remix the earlier example … you have the lawful good lawman who always brings in his guy alive because they should stand before a judge and jury. He’s never killed and never will. Then he does when his son is threatened. Now a lot of readers might find that reasonable because of our understanding of family bonds, but you want to set that up in the story. Show how close he is with his family. Have a minor threat happen earlier in the story for him to break his cool over. The reader may not straight out know the character's breaking point before it happens, but it should feel natural once they get to that point. There would have been hints. We should’ve maybe guessed a second before it happens. Like plot twists, character twists should make sense in retrospect. Conclusion Those big, defining moments for a character, good or bad, have to be earned. They have to be deserved. These are the results of character development. Background:

In 2017, I entered a Maryland-based writing contest and ultimately had my short story submission “The Pawn Shop of Intangible Things” place second. It was a pretty amazing experience that has involved an awards ceremony, a nice check, and free admission to a sci-fi writing conference where I read my story on a panel. Last but not least of all the honors, I was asked to be a judge for the 2018 contest. Process: I was sent the five finalists' stories that had been selected by the first round of readers. With the other finalist judges I was charged to rate each story between 1 and 10, and those ratings were be compiled and totaled to determine the first, second, and third place stories. I was also able to write commentary that was sent to the authors. The Experience: While I gladly volunteered, there was a little dread when I received the attachments of the stories in my inbox. See, I have a Bachelors in Creative Writing, and if you are familiar with creative writing classes you might know that they are usually done in the workshop model. We would read two to three of our classmates’ stories in preparation for each class, write critique letters, and discuss them in round table fashion during class. I read a lot of boring, not good, and pretentious stories in my pursuit of that degree to the point where I lost all perception of what was good and what wasn’t. Had I just volunteered to relive that experience and read through five dull stories? I clicked on the first one, opened it, read the first line and had my fears realized. The line was outright amateurish -- bland and generic. I was back in undergrad. Thankfully, that did not end up being the case. After reading the story in full -- although avoiding it by saving it for last -- it did improve once it got into the story proper. It was still a weak opening, but fears did not realize completely. What I ended up doing was reading five stories ranging from decent to heart-eyes-emoji (that’s the technical scale) and learned a lot from it. What I Learned: Point 1: Story is King. The story I subjectively thought was the best wasn’t the one with the best prose. It was the one with the best story. Of course, story is both concept (but ideas are cheap), and the execution of that concept. Point 2: Execution makes all the difference. All the stories had interesting concepts. The contest was SF/F focused, so they were ‘high concept stories.’ Listen: AI’s as narrators, folk tale demons, space-time travel, visions of the future, and werewolves. Come on. That’s a goldmine. But as I (and of course many before me) have already stated, ideas are cheap. It’s all about how you present those ideas. As one would expect, to get this far in the competition all were competent stories. It’s that fine polish of execution that makes a difference between competent and awesome. Language and prose are part of the execution: the narrative strategy of POV, timeline, voice, and what not. When to start the story and when to end it and when to hit the other beats in between. All important. Point 3: Setups and Payoffs are a balancing act. Reading this selection of stories, one aspect of execution I became very aware of was ‘setups and payoffs.’ My favorite ‘heart-eyes-emoji’ story was a well-paced space adventure with the setups and payoffs interwoven from the first page to last. In contrast, there were stories with not enough setups, or not early enough, sapping the pay off of its power. There were stories that had a lot more setups than were ultimately paid off, which is like having a question without an answer. That balance is so important to the reader because a story needs to make sense. It’s like laying out the clues in a mystery novel. All the plot workings need to be laid out for the reader bit by bit. Point 4: Pacing is Important. Like setups and payoffs, good pacing is essential to a well-balanced story. I saw one particular pacing hang up occur over a few of the short pieces I reviewed. The stories were… front-heavy. They spent too long in the beginning on things that weren’t the main point of the story. One of Kurt Vonnegut’s great pieces of writing advice is “Start as close to the end as possible.” Every writer should take that to heart. I often think about this, if not in the drafting stage, than the editing stage. (It’s very common in first drafts to start too early.) To bring back another memory from my undergrad creative writing days, I recall how often a particular fiction writing professor of mine would often instruct students in workshops that their story actually started on page three, or five, or nine. There was always some sort of silent-eyed horror that passed over the face of whoever’s story it was, because there was a lot of hard-worked prose in there they were being asked to cut, but it was an important lesson. Remember you can integrate backstory in a lot of ways without starting at the very beginning! My heart-eyes-emoji story dropped the reader right into the moment. All the world-building and character growth were part of the actual scenes. Point 5: The Little Things Don’t Matter (When Everything Else is Right). There will always be stuff to nitpick. There will always be an awkward sentence, or a moment that could’ve been tweaked to be stronger. But when a whole story is a strong, compelling, and well-balanced all the nitpick-y sand falls from your eyes as a reader. You're too engaged being carried along by a well-crafted story to let the other things ruin the experience. Conclusion So… that’s what I learned. Maybe other people judge stories for competition by other criteria. Maybe they have a checklist or grid, giving out points to certain factors like this was an episode of Chopped: Presentation, Taste, and Creativity. I read with my intuition. I can never exactly turn off my writerly brain when reading, seeing the tricks of how a writer pulls off a certain twist or thinking how I would’ve differently. I acknowledge there is always a measure of personal taste in something like this and any judging of the creative arts is subjective. However, we humans are storytelling animals. We are surrounded by stories from birth on -- books, movies, television shows, the stories we tell each other, narratives in video games and other media, and on and on and on. We love a good story and absorb some feel for when a story works or when it feels off. We might not all be able to identify exactly what is off, or have the vocab for it, or be able to analyze it or write it ourselves, but we have the intuition. I was glad I was able to use my storytelling intuition, in combination with my learned and practiced knowledge of creative writing and literary analysis, to learn about making and reading a good short story. |

Margery BayneInsights from the life of an aspiring, struggling writer; a passionate reader, and a working librarian. Archives

June 2022

Categories

All

This website uses marketing and tracking technologies. Opting out of this will opt you out of all cookies, except for those needed to run the website. Note that some products may not work as well without tracking cookies. Opt Out of Cookies |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed